The truth of this has been confirmed by the courts, as well as numerous lawyers we spoke with, who provided us with several lawsuits, statements of claim, judgments, and revisions, all emphasizing the same thing: Bank of Srpska went bankrupt, preventing them from being compensated as mandated by law.

It’s said that a large number of citizens have suffered due to this situation and are astonished that, regardless of how unserious the state may have been, it allowed such funds, which are untouchable and must be safeguarded for citizens until disputes are resolved, to vanish.

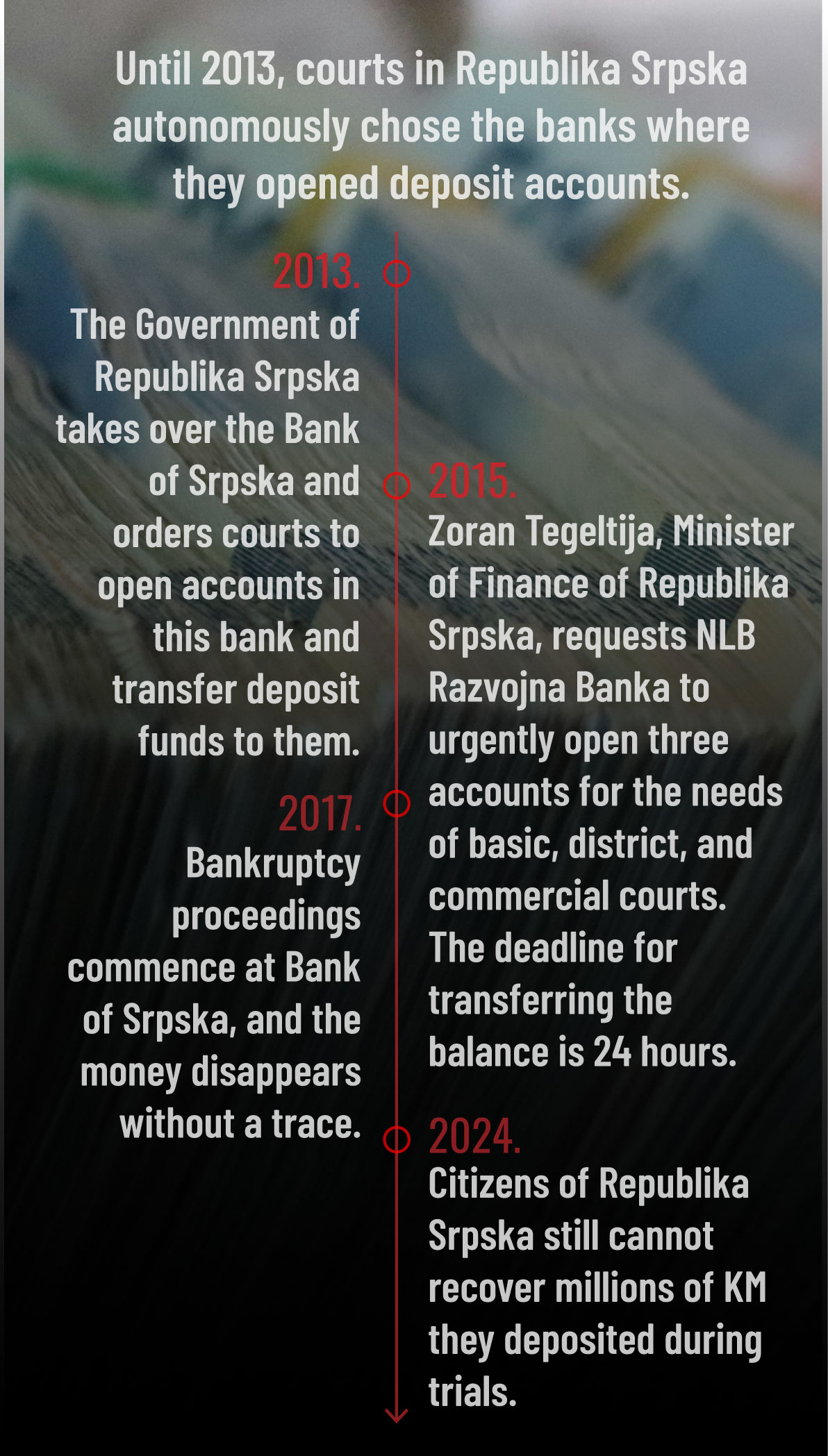

Lawyers mention that before the establishment of the Bank of Srpska, each court in the RS had its own account in a bank of choice, where parties in proceedings deposited funds during the process, for example, for the partial payment of some property, after the sale of disputed items, maintenance, and similar expenses, which would be paid out to the prevailing party after the judgment.

After the Government of RS took over the Bank of Srpska in 2013, a decision was made for all funds to be deposited into an account at this bank, consolidating everything in one place. Courts were obliged to immediately open accounts in this bank and transfer funds.

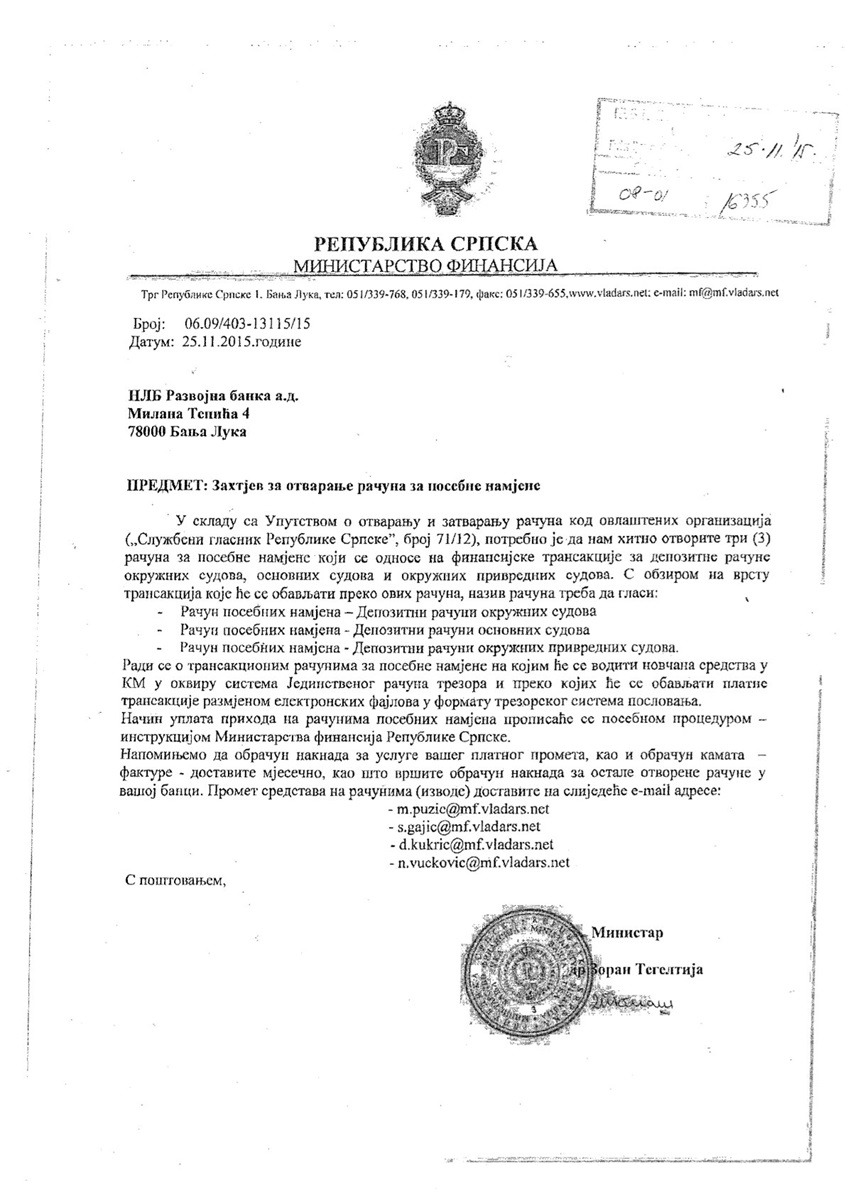

However, two years later, the then Minister of Finance, Zoran Tegeltija, requested NLB Razvojna Banka to urgently open three accounts for the needs of basic, district, and commercial courts for these purposes, with a 24-hour deadline to transfer the balance.

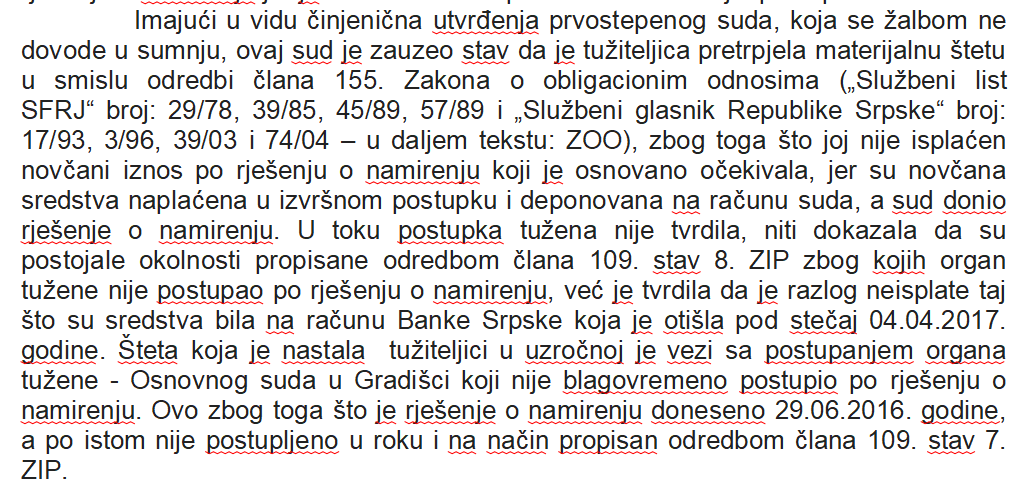

With the initiation of bankruptcy proceedings against the Bank of Srpska in April 2017 due to financial problems and a debt of 121 million KM, every trace of this money vanished, and the public had no information about it until now. Meanwhile, lawsuits from citizens, in whose favour judgments were rendered, are reaching the courts, demanding the payment of what was awarded to them.

Miron Bjelovuk, a lawyer from Gradiška, told eTrafika that, in his opinion, this is a major scandal that went unnoticed by the public, with the money disappearing and citizens being deprived of their property, which is legally treated in a special manner.

Bjelovuk says that court deposits should be treated as funds placed in a specific safe and withdrawn from it exclusively through a certain procedure. This was how it operated until 15 years ago when banks entered the scene.

“So, claims were preserved in enforcement proceedings, for example, in cases of child maintenance. For instance, if a court seizes a Mercedes car from one parent and sells it for 20,000 KM. That money doesn’t immediately go to the mother and child; instead, it’s deposited in a safe, waiting for the scheduled date set by the judge, when the money is withdrawn from the safe and paid to the mother, a fee is given to the expert, and so on. Now that money is no longer there, and that mother, already exhausted from litigation, has to sue the state and enter a new battle for something that was already awarded to her,” explains Bjelovuk.

Absurd upon Absurdity

Another example illustrates the absurdity further, involving a client from Gradiška with claims totalling around 470,000 KM. A property was sold, with a bank being the plaintiff. The money was deposited during the dispute and vanished along with the Bank of Srpska.

“Then comes the absurd upon absurdity. After the judgment, the bank demands its money, but the judge can’t order the payment because there’s no money. The judge then asks the accounting department to find a solution for payment, consults the Ministry of Finance, and then receives a response that the funds weren’t budgeted, therefore no payment can be made. Can you imagine that? As if it’s a utility bill! It’s their money, and they can’t access it even though the court ruled. I know many have sued, and I wouldn’t be surprised if there are far more cases than we think,” says Bjelovuk, adding that both citizens and courts are powerless due to this situation.

The bizarre scenario and manipulation of citizens’ property don’t end there. After the collapse of the Bank of Srpska, the deposit money was transferred to an account in a commercial bank, which by the nature of its business, circulates the funds it has at its disposal, which the law expressly prohibits.

“If I, back when I worked as a court secretary, had taken, for example, 2,000 KM from that safe to fix the official car, I would have committed a criminal offence and would have been held accountable for it, even though I would have reimbursed that money within ten days, as it would have come from the budget. Now, a separate account for the court’s operations is opened in commercial banks, and as soon as the funds are deposited, they are circulated further. The court now hands it over to banks to circulate, even though it was given for safekeeping purposes, not for business risk,” says Bjelovuk.

Another lawyer, who prefers not to be named to protect his client, mentions that the amount of the deposit being sought is in the millions, dating back to 2015.

Some Deposits Exceed Million-KM Amounts

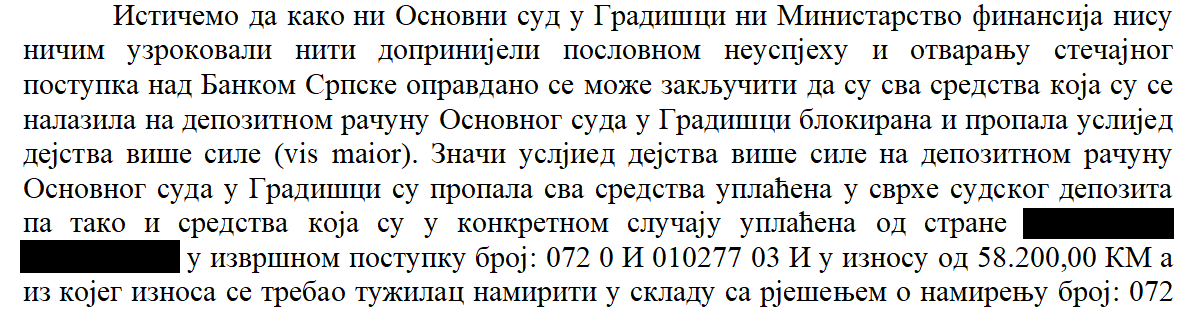

“The first-instance court determined that the Ministry of Finance issued an order to terminate deposit accounts, and Bank of Srpska, in bankruptcy proceedings, ‘swallowed’ 1.7 million KM belonging to my client. We requested the return of the deposited amount from the Ministry of Finance and appealed the insistence on depositing funds into the Bank of Srpska, even though it was already drowning in debt,” the lawyer explained.

According to unofficial information we obtained, Banja Luka’s Basic Court lost around five million KM in deposits, while the Basic Court in Gradiška lost about half a million.

Officials from the Basic Court in Bijeljina confirmed to us that they also lost funds with the Bank of Srpska, totalling 1,299,114 KM.

“In disputes initiated by parties before the court, payments were made as advances, to the court’s deposit accounts opened with banks, including the deposit account opened with Bank of Srpska, which was subject to bankruptcy proceedings,” they said at this court.

The deposits of the Basic Court in Trebinje are also stuck, with 395,529 KM remaining in the account of this bank.

“The balance on the deposit account with ‘Bank of Srpska’ according to the business records of this court as of December 31, 2015, amounted to 395,529 KM,” the court briefly stated, adding that within the unified treasury account, deposit accounts for basic courts were opened with “Nova Banka” Banja Luka and NLB “Razvojna banka” Banja Luka.

The District Court in Banja Luka confirmed that they do not have funds, and the amount they provided in their responses is slightly lower than the information we received from our source, totalling exactly 4,965,470.25 KM.

Only the Basic Court in Banja Luka responded to our inquiries, informing us that they were obliged to conduct judicial operations through the treasury system of Republika Srpska, i.e., via deposit accounts, all in accordance with the then-applicable Treasury Law.

In that regard, the Ministry of Finance of Republika Srpska, by order dated December 30, 2013, opened deposit accounts for all basic courts, which were required to conduct deposit operations with parties through these accounts.

The Ministry of Finance issued an order on December 30, 2013, to terminate the deposit accounts of the basic, district, and commercial courts of Republika Srpska, and these budget users would conduct their operations through the unified treasury system. The obligation of the basic, district, and commercial courts was to transfer the balance by December 31, 2013.

“The balance on the account was 3,113,121.97 KM. Bank of Srpska a.d. Banja Luka, chosen by the Ministry of Finance RS to be the bank through which basic, district, and commercial courts would conduct business with parties, subsequently went into bankruptcy, and since then, the court has not had control over those funds. Regarding how this came about, we refer you to the competent Ministry of Finance of Republika Srpska. Regarding the operation of deposits, the court processes withdrawals from the deposit account based on a court decision provided by the presiding judge to the court’s accounting department,” said officials from the Basic Court in Banja Luka.

We also asked other courts in Republika Srpska about the deposits, but responses did not arrive by the conclusion of this article. The Ministry of Finance RS also did not respond, so we will publish their response later if it arrives.